Free-market individuals believe industries should be allowed to do whatever an unregulated market allows. Most would object to Therapeutics Initiative (TI). But many of us recognize its value. TI is part of the Department of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology & Therapeutics at UBC’s Faculty of Medicine. It aims to provide health professionals and the public with evidence-based information on healthcare interventions. TI is independent and separate from the government, the pharmaceutical industry, and other vested interest groups.

Its work:

- The Therapeutics Letter, a bimonthly publication targeting problematic therapeutic issues.

- The Drug Assessment Working Group (DAWG) analyzes scientific evidence on the effectiveness and safety of drug therapies. The DAWG reviews and appraises research relevant to new and existing drugs.

- The PharmacoEpidemiology Group (PEG) conducts research on prescription drug utilization, epidemiological research methods, the evaluation of drug policy and educational interventions, and drug safety and effectiveness.

- The Therapeutics Initiative Blog provides news and information from the world of therapeutics.

Annual sales of medicines in Canada amount to about $50 billion. In the USA, the total is close to a trillion Canadian dollars. No wonder that powerful commercial interests dislike organizations like UBC’s Therapeutics Initiative. A decade ago, Christly Clark’s BC Liberals were trying to eliminate or cripple TI. I wrote about government actions against TI several times before.

My attention was drawn again to Therapeutics Initiative when I was seeking information about a drug in my medicine cabinet. Gabapentin, also known as Neurontin, was first licensed in Canada in 1993 for the treatment of focal seizures. By the end of the 1990s, unapproved uses of gabapentin were numerous. It was being prescribed for neuropathic pain, migraine, mood disorders, and other ailments.

Gabapentin is one of today’s most widely prescribed drugs. A 2009 Therapeutics Letter reveals how it came to be that way. Excerpts:

…U.S. litigation has revealed that Neurontin’s off-label promotion was assisted by selective publication and citation of studies with favorable outcomes…

Gabapentin never achieved major commercial success as an anticonvulsant. In 1995 Parke-Davis marketing staff proposed an experimental program to test anecdotal claims of efficacy for “neuropathic” pain and other syndromes. Research results were to be published, “if positive.” Immediately after the 1998 JAMA publications, Parke-Davis launched a program of selective publication and intensive marketing, assisted by “Key Opinion Leaders” (KOL) Sworn testimony indicated that Parke-Davis used its “clinical liaison” sales representatives and “Key Opinion Leaders” to market Neurontin “for everything”. By 2003 annual U.S. sales of gabapentin had expanded from $98 million to $2.7 billion/year.

UBC’s Dr. Tom Perry provided his expertise to an American legal action. It included this:

Based on a thorough and scientifically valid analysis of all relevant double blind randomized clinical trials (DBRCT), Neurontin is not an effective drug for the treatment of neuropathic pain. My thorough review and meta-analysis of available published and unpublished evidence shows that Neurontin (gabapentin) has at best a clinically insignificant average effect on pain scores. The proportion of patients who recognize “improvement” on a Patient Global Impression of Change scale at the end of studies is roughly matched by the proportion of patients who experience adverse events. In the real world, to which the concept of “effectiveness” applies, patients taking Neuronntin (gabapentin) should be expected to accrue less benefit and more harm. Thus, in my opinion, Neurontin (gabapentin) has not been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for pain.

In 2004, Pfizer pleaded guilty to several civil and criminal charges for illegally promoting the off-label use of gabapentin. The company paid hundreds of millions of dollars in penalties. But off-label sales of gabapentin continued to soar despite evidence it lacked effectiveness for some of the problems it was used to treat.

Later studies found in the Cochrane Library showed Gabapentin is helpful for some people with chronic neuropathic pain. Still, knowing beforehand who would benefit and who would not is impossible. The evidence was mostly of moderate quality.

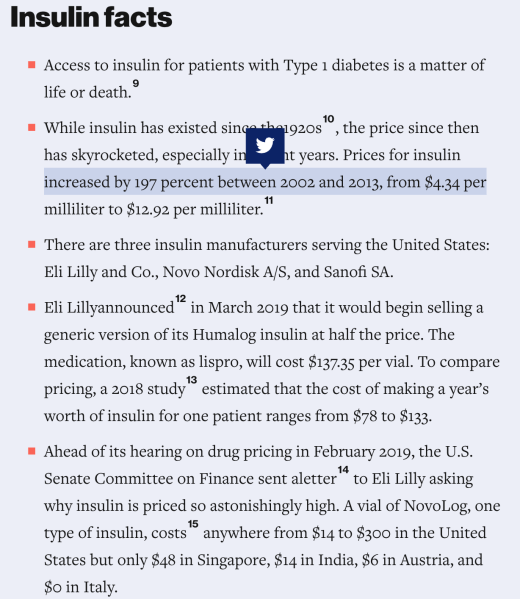

Corporations tell us that high prices are necessary to fund research and develop new life-saving drugs. The evidence tells a somewhat different story. The American experience with insulin is revealing. The medicine was developed more than 100 years ago at the University of Toronto. In 1923, the discoverers sold insulin patents for $1 each to the U of T.

The following is submitted by a reader:

Mr Farrell,

Is it the iceberg problem? The risk is from what you can’t see below the surface,…

Regarding your piece on Big Pharma’s heartfelt determination to contemplate profits first, human lives if profitable sometime later, POLITICO focused on the EU and wrote the following:

The EU butts heads with Big Pharma to make medicines cheaper

The EU wants to give European consumers access to more medicines, faster, and for less money —and it’s picking a fight with the pharmaceutical industry in the process.

A draft plan to overhaul the EU’s pharmaceutical laws — a copy of which has been obtained by POLITICO—would see the European Commission rip up the perks that drugmakers currently enjoy in order to let unbranded rivals enter the market earlier, driving down prices for consumers.

It proposes slashing the amount of time that pharmaceutical companies have to sell their medicines without competition. At the moment, companies that develop branded medicines have 10 years to sell a new drug unchallenged, after which rivals can launch unbranded “copycat” drugs that quickly drive down prices — and profits.

And here:

How Big Pharma games the system — and keeps drugs prices high

The pharmaceutical market is a strange beast.

It’s governed by a complex system of rules that protect new branded drugs from unbranded rivals for a limited period of time, in order to keep these cheaper generic competitors at bay.

But measures such as patents, market exclusivity and data protection — designed to give pharma companies the chance to recoup investment in a new drug — are being exploited by some Big Pharma to keep competitors out of the market far beyond the intended fixed period of around 15 years, argues the generics sector.

The Conversation added more:

When big companies fund academic research, the truth often comes last

Industry sponsors suppress publication

An early career academic recently sought my advice about her industry-funded research. Under the funding contract – that was signed by her supervisor – she wouldn’t be able to publish the results of her clinical trial.

Another researcher, a doctoral student, asked for help with her dissertation. Her work falls under the scope of her PhD supervisor’s research funding agreement with a company. This agreement prevented the publication of any work deemed commercial-in-confidence by the industry funder. So, she will not be allowed to submit the papers to fulfil her dissertation requirements.

Big Pharma: How the World’s Biggest Drug Companies Control Illness

Tracing the development of the modern pharmaceutical industry, Law correctly cites the failure of what she calls “the deal”—a regulatory framework broadly based on the idea that pharmaceutical companies always produce worthwhile products that society will automatically buy. In hindsight, of course, this settlement seems woefully optimistic. But it is important to remember that it came about at a time when companies really were producing innovative medicines relatively easily; when such development was affordable; when patients were passive and trusted doctors; and when doctors trusted the medicines. And even now, as the book makes clear, the guiding principles of the deal remain in place, despite being increasingly unfit for purpose.

A key example in the UK is the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme, the unique, grotesquely brilliant arrangement that dictates how much overall profit a major pharmaceutical company can make through sales of its brand-name products to the NHS. The scheme helps to control the national drugs bill. However, it also deliberately uncouples the price set, and the profit made on, an individual product from the costs incurred in developing, testing, and promoting that product.

… and what can we expect Canada to do?

Pls. Advise.

Categories: Health

Whether it’s government or business, any time the word big is used, it’s a pejorative.

The paradox here is that to effectively deal with big pharma, big government is now required.

Big balls on that government instead of big bags would help.

LikeLiked by 1 person